“Sassy Chap Games,” a studio of voice actors-turned-game developers launched “Date Everything” in June, a lighthearted title aimed to make space for everyone. With over 100 unique characters and thousands of choices, players can truly date anything and everything they please.

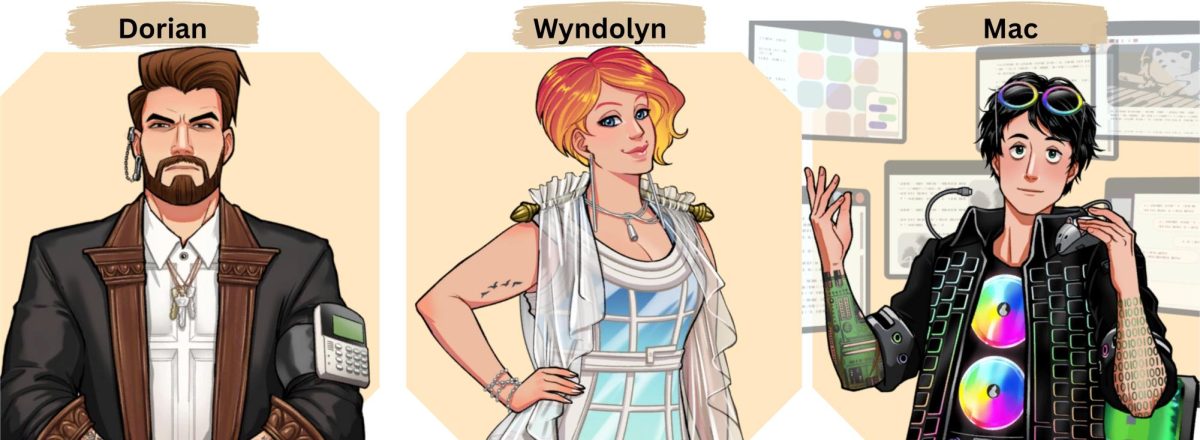

You play from as the main character, struggling with your 9-5 remote work and desperate. You get a mysterious message from a user on “Thiscord,” who, after some back and-forth, delivers a pair of special glasses to your house for testing. The glasses, called the “Dateviators,” turn every object into a humanoid, dateable version of itself. Your first interaction with a “Dateable,” as the characters are called, is Skylar, the dateable version of the glasses. Each design incorporates aspects of the object they are based on, usually having corresponding names— Dorian, Wyndolyn and Mac are based off a door, window and computer respectively.

From a shallow perspective, the game premise is cute; it is a dating simulator geared towards LGBTQ+ representation and inclusion, with transgender characters and polyamorous relationships—the concept of cheating is not a problem within the storyline. However, certain aspects of the game led to splitting opinions.

One of the biggest points of discussion involves Mac, a character who uses a wheelchair. Early versions of the game showed Mac with an unrealistic mobility device that disabled players and advocates quickly criticized. Typically, these complaints and concerns are not addressed, but the developers of “Date Everything” redesigned Mac’s chair, giving them a model more accurate to real wheelchairs. The redesign earned praise across social media. Many players said they appreciated seeing developers listen and take feedback seriously. For gamers with disabilities, the change meant more than cosmetic polish— it gave them a character who felt thought.

While the update improved representation, “Date Everything” struggles where it matters most: the dating. The game opens with cringey, millennial humor and an overwhelming number of options, but the actual romances stop too quickly. Once players choose to pursue a relationship, that character’s storyline ends.

Critics argue that this abrupt conclusion undercuts the point of a dating simulator. The genre usually thrives on gradual relationship building, branching dialogue and the unfolding of intimacy. Here, the fun ends just as it should begin. Some fans defend the structure, claiming the game works better as a narrative anthology of short stories rather than as a traditional romance simulator. Others say the shallow progression makes the central promise of the game feel hollow.

Despite those complaints, “Date Everything” succeeds in pushing conversations about inclusivity and accessibility forward. The developers’ willingness to adapt and improve Mac’s design shows an attentiveness that many studios lack.

As a result, the game works best as an experimental piece. It is a collection of stories about love in many forms, paired with a rare example of a studio listening to its players. Just don’t expect a fully satisfying romance once you find the character you like.

Also, your character cannot jump. Good luck passing the time.