“Good Boy” isn’t just another haunted-house story; it dares you to experience fear through the eyes of a dog. From the opening frames, director Ben Leonberg grants us a perspective rarely seen in cinema, where Indy, the film director’s dog, becomes the central witness to the horror creeping inside a quiet home.

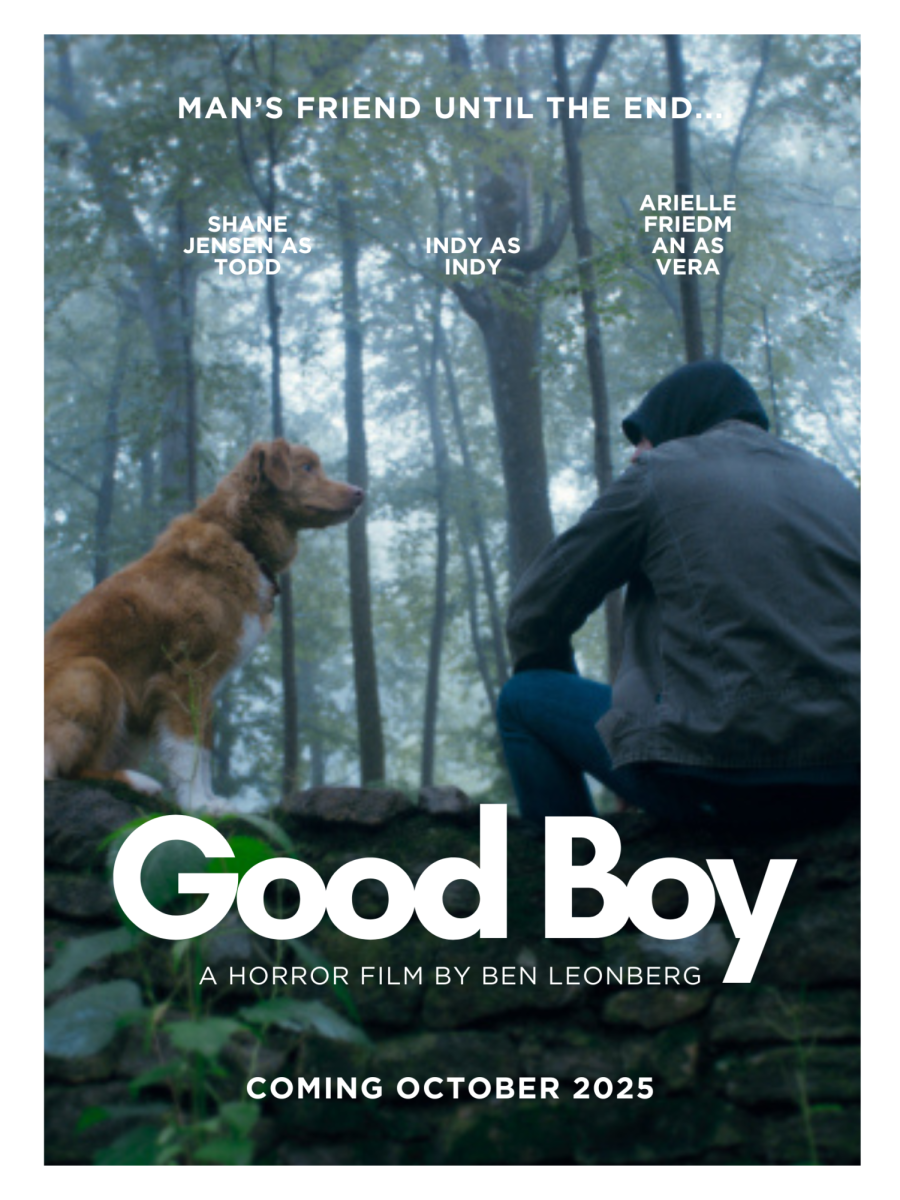

The film, which premiered at South by Southwest (SXSW) earlier this year and is now distributed by IFC Films and Shudder, stars Shane Jensen as Todd, Arielle Friedman as Vera, and genre veteran Larry Fessenden in a supporting role. At just 73 minutes, it moves quickly, wasting little time before letting Indy command the screen. Todd has relocated to his family home after a health crisis. While he tries to settle in, Indy begins noticing odd disturbances. Shadows shift, noises echo and the dog’s unease grows. Todd dismisses these reactions, as most owners might, until it becomes clear that Indy may be the only one truly aware of what lurks inside the house.

What makes the film extraordinary is Leonberg’s choice to work with Indy as he is, unscripted and unenhanced. Unlike most animal-centered films, Indy is never anthropomorphized. He doesn’t “perform” tricks for the camera or speak with human expression; instead, his natural reactions drive entire scenes. The cinematography emphasizes his perspective, often keeping the camera low to his level and cropping out faces, forcing the audience to see the world the way he does. The sound design deepens the tension with subtle creaks, muffled footsteps and stretches of silence that make Indy’s stillness as nerve-wracking as any jump scare.

The result is both intimate and unsettling. At its core, “Good Boy” is about loyalty and the ache of being unheard. Indy perceives threats long before the humans around him do, but his warnings go ignored. That frustration—watching someone you love sense danger yet being powerless to help—gives the film emotional weight beyond its scares.

Still, the movie isn’t flawless. At times the narrative feels thin, leaning heavily on mood rather than deeper story development. Some viewers may leave wanting more explanation of the supernatural forces at play. Yet the simplicity works in its own way, keeping the focus on Indy’s devotion and the eerie stillness that builds suspense minute by minute.

For me, the tension came less from traditional horror tropes and more from waiting with Indy, watching him watch. Every pause and every glance made me lean forward, anticipating something I couldn’t see but knew he could. That gamble—putting a real dog at the center of a psychological thriller—pays off, even if it requires patience from the audience.

The uniqueness of “Good Boy” becomes even clearer after the credits roll. Leonberg himself appears on screen to share a final thought: many owners wonder why their dogs stare at blank walls, bark at nothing, or freeze as if they sense something unseen. This film embraces that idea and asks viewers to consider whether those moments of canine alertness are meaningless quirks or signs of something we fail to perceive. It’s a clever way to tie the film’s central question back to everyday experience, leaving audiences with a shiver that lingers beyond the theater.

In a genre saturated with cheap scares and CGI spectacle, “Good Boy” distinguishes itself with restraint, intimacy and a surprising amount of heart. It’s a horror film about shadows and silence, but also about trust and loyalty. Whether you come for the chills, the experimental camerawork, or simply to see a dog carry a movie on his own, this film offers something rare: a story that makes you watch, wait and wonder alongside a companion who has always been by our side.